- Home

- Rabia Gale

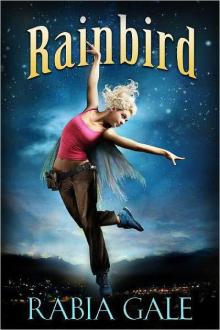

Rainbird

Rainbird Read online

RAINBIRD

Rabia Gale

She’s a halfbreed in hiding.

Rainbird never belonged. To one race, she’s chattel. To the other, she’s an abomination that should never have existed.

She lives on the sunway.

High above the ground, Rainbird is safe, as long as she does her job, keeps her head down, and never ever draws attention to herself.

But one act of sabotage is about to change everything.

For Rainbird. And for her world.

Rainbird is a fantasy novella of about 31,000 words.

Published by Rabia Gale

Cover art and design by Ravven

Smashwords Edition Copyright © 2012 by Rabia Gale. All Rights Reserved

This e-book is licensed for your enjoyment only. No part of this publication may be reproduced, distributed, or transmitted in any form or by any means, including photocopying, recording, or other electronic or mechanical methods, without the prior written permission of the publisher, except in the case of brief quotations in reviews.

This book is a work of fiction. Any resemblance to persons, living or dead, is purely coincidental.

Table of Contents

Rainbird

Acknowledgments

About the Author

More Books by Rabia Gale

Rainbird

Rainbird danced on the sunway to the singing of uncountable stars, music that only she could hear. Her trench coat, too large and shabby, smelling of cigar smoke and mothballs, flapped around her. Under the thick thirdhand fabric, her wings whispered, satin-starch-slither. Her long-toed bare feet skimmed the bumpy bone of the sunway, worn smooth and glittering by centuries of inspection. Her oversized lungs pulled in the thin cold air.

Rainbird rose up on her toes, spun, leapt high and proud like a horse, and landed perfectly. She dipped her head and knees in a curtsey to her celestial audience. Then she kissed her hand to Glew, the dim, faraway true sun of the purebred eiree. It glowered with sour malice, rheumy-eyed even this far above the clouds and the smoke, the haze and the lights of the cities of men.

Her gesture was theatrical, less a reverence and more a flirtation, though not entirely without affection. Glew had witnessed her solitary dances for two years, since she had first come up on the sunway. It and the other stars had replaced the human audience that had gaped and cheered during her performances in the circus she’d grown up in.

No, she’d been drawn to the stars, both the fixed and the wandering, even before she’d escaped to the sunway. She’d watched them from downside, in the Deeps of the night, perched atop the circus tent, above a sawdust floor covered in trampled-on confetti, empty paper packets, and the sequins and flowers that had fallen unnoticed, like dandruff, from the performers’ costumes.

She had not danced, then, only listened to the stars’ music. Now, she closed her eyes, twirled, and lifted her arms up, as if to embrace them.

“Never draw the attention of the stars.” The voice was as cold and as quiet as snowflakes. “For you will only live to regret it.”

Rainbird’s eyes snapped open. She spun, looking wildly about her, but there was no one next to her, no one on the vast expanse of ivory bone all around her. Then she looked up, into the air, and made out a shadow upon the cable that stretched overhead. An eiree wire, made as a rest stop for the winged race, a sop from the humans for bundling the eiree off the dragon spine that formed the sunway and onto the skeletal remnants of the creature’s wings. She had never seen an eiree upon one before.

Until now.

Rainbird kept still, tense and wary, not speaking. Maybe the eiree would not know her, would not know that she was the halfbreed. Her wings were hidden and…

“I have watched you, little worm.” Contempt would’ve been better than the disinterested coldness which dripped into Rainbird’s bones. “You do not know that which you meddle with.”

So he knew her, did he? He watched her, did he? Well, let him see this.

With a toss of her head, a flick of her wrist, a spinning kick, Rainbird banished the eiree prohibition. She was not eiree, had never been recognized by them as such, didn’t want to be claimed as one of them, and she would not live by their rules.

She owed them nothing.

A reckless anger burned through her blood. She knew that Petrus would want her to say nothing, do nothing, but all caution was swept away by that hot tide.

“See here!” Rainbird called up to the stars, singling out her favorite, a wanderer with a reddish tinge. She didn’t care if the eiree saw her. She hoped he did. “Watch!”

She gave that star her most daring leaps and her most artistic turns as the celestial chorus rose to a crescendo. Let the eiree break law and attack her on the sunway for her defiance. Let the stars be unimpressed as they always were. That only spurred her on to more impudent and far-reaching feats.

But at the highest point of her leap, the reddish star looked at her.

Looked. At her.

Rainbird touched down, stumbling, shaken. But no, it was not her balance at fault—the sunway itself shuddered. A tremor. They’d become common enough this past year, but never at night when the Day Sun was down.

A whisper brushed across her ears, “…am…coming.”

Papa! Guiltily, Rainbird reached for her radio, her one concession to Petrus’ caution. But no, it hissed quietly to itself, channeling nothing but static. Bone quivered under her feet again, as if the massive beast whose spine she stood upon stirred in restless sleep.

“No,” she said, out loud. “No. The dragon’s been dead for centuries, before humans even came to this world.”

Then she looked up quickly, half-expecting the eiree to say something cryptic and disturbing, as was the wont of his kind. But there was no one on the wire.

She was alone again.

Rainbird rubbed at her eyes, gritty with lack of sleep. The Company did not like sunway tremors. They had already delayed sunrise and roused the inspectors out of their eggs, tucked warmly in the discs between the spine segments, to inspect every foot of track on the underside of the sunway.

Static shrilled from her radio, resolved into Petrus’ voice. “You there yet, Grit?”

That was her cover name. “Yeah,” she growled back. They kept their radio communications terse and on topic. Anyone could be listening.

“Get the equipment ready. I’ll be there soon.” Petrus’ voice was tight with tiredness and the need to keep from coughing. He clicked off before she could respond.

He shouldn’t be out here. Stupid sunway tremors!

He’d told her to wait. He expected her to wait.

I’ve been doing this for years by myself! And the sooner we finish, the sooner we can go home. He can go home.

Rainbird shed her coat and kicked it aside, up against one of the spines that marched in a row along the top side, the nightside, of the sunway. She wore thick pants reinforced with leather panels and a halter top which left her powerful shoulders and arms bare and her wings free. They rose from her shoulders in thin, diaphanous layers, and hung raggedly to her knees. A true eiree was light and strong enough to fly, but a halfbreed—even had her wings been whole, and with her strength and acrobatic skill—could not.

However.

Rainbird pulled the harness over her head and settled it against her shoulders and back. She cinched the straps tight around her waist and twitched her wings to make sure they were unconfined. Twisted poly ropes clipped onto the harness, their other ends secured to rings embedded deep in the bone.

She stood at the edge of the sunway where it curved down, and stared at the darkened land. Faint pinpricks of light came from some town below. The darker roads and rivers ran like uncoiling ribbons. Far beyond her sight, the sunway sloped down t

o a shattered tail in a canyon on one side and a skull buried in a swamp on the other. Crumbling high cliffs and shattered stone mountains ringed the crater the dragon had made on its impact.

Rainbird turned her back, looked out at the gritty cream bonescape instead. She was half off the edge.

She jumped.

Most inspectors did not jump. Most inspectors scuttled down, paying out the rope, boots scuffing against bone, edging their way to the track on the underside, the sunside.

None of the other inspectors had wings. None of them had a drop of eiree blood. None of them wanted to fly.

Freefalling in the cold, plunging into darkness. Wind roared in Rainbird’s ears, pierced her soft downy skin and plunged into her light hollow bones. Her tattered wings streamed behind her. She relished the way her skin prickled as the icy air rolled over it, the way every sense was sharpened, the way everything took on clarity and brightness. A knot of excitement and panic in her stomach wriggled, like a nest of snakes.

This was what it meant to be truly alive.

The end of the tether jerked her back to her duties. She’d been bracing for it, and she brought her feet up in time to meet the sunway. Smack, smack, several times, swinging back and forth until she’d managed to slow herself down enough to reach for the hand and footholds sunk into the bone.

One of these days, Petrus often said, she’d crack her skull doing this.

Since today was not that day, Rainbird unwound yet another rope from her waist and clipped another safety line to a ring. She went down swiftly, till she reached the metal track that ran all along the underside of the sunway. It was made of a virtually indestructible alloy of iron and serpentium, nearly as invulnerable as the bone itself. Even at this high altitude, subject to the fierce heat of the Day Sun as it glided across the track and the bitter cold of the night, the alloy held its shape remarkably. But not so well that she was out of a job.

Or more accurately, her father was out of a job.

Their occupation was not exciting, unlike the glamour and theatrics of the circus that had been her first home. Once she’d danced on the high wire and hung on the trapeze, her vestigial wings sparkling with glitter, disguised as a costume. Now, she tested rivets and crossbars, welded together tertiary supports of inferior alloys with a blowtorch, lubricated the insides of the track with gallons of oil.

Having to do all of this virtually upside down, several markers above the earth, just added a touch of spice to the whole endeavor. Luckily, she was not slowed down by thick gloves or a tank of supplemental oxygen.

Rainbird unclipped the safety lines from her harness and belt, and left them dangling. She wrenched open a small door in the giant track, then wrestled it shut behind her. Beyond the small space was another door. Rainbird waited for the pressure to re-equalize before opening it. She squeezed in through the small space and dropped onto a wire-mesh floor.

The air was sharp with lubricant, sooty with the recent application of a blowtorch. Underneath it all was the musty, organic scent of ancient bone, radiating heat and thrumming with electricity. Far above Rainbird’s head, above the metal framework of the track, strung through holes in the bone segments was what remained of the continent-sized dragon’s spinal cord, co-opted now to run messages and electricity throughout the sunway.

Did any of the creature’s thoughts, reflexes, or instincts still remain in those nerves? She’d heard of experiments with frog legs; some speculated that those same electric currents were responsible for the tremors, activating ancient muscular tissue that had survived both time and the humans.

Rainbird shivered at the idea, and turned her attention to the track. She made sure that a thick film of lubricant covered all surfaces in contact with the Day Sun as it glided through, and zealously banged on supports to ascertain their soundness. She carefully checked the places where metal embedded into bone, looking for any distortion or cracking.

Petrus Gallavant had never had an X on his record for negligence of duty. His daughter was not going to ruin that for him.

Rainbird climbed up the inner walls of the track, scooting from ladder to ladder in her quest for weakness. A pungent whiff stopped her.

Sunmoss! Rainbird grinned. Her day had already gotten better, maybe enough to make up for last night’s encounter with the eiree and the summons from Headquarters that had taken Petrus from his sickbed. There it was, a yellow-gold mass, tucked in a corner, rooted in the bone. The thermosynthetic moss thrived in the heat that the track captured during the Day Sun’s passage. It was rare to find some growing naturally, but it would fetch a good price in the Up-High Market on Third Rib.

It was tricky getting to the sunmoss, tucked away as it was in the bone, away from the scaffolding built around it. Rainbird crawled onto the edge of a metal limb, stood up and reached. She had just enough give to scrape off some of that precious stuff, the feathery golden moss flaking into her hand.

Along with something else entirely, something grey and speckled, like dandruff, spiraling down in motes.

Bonerot.

Rainbird stared at the evidence in her hand, breath squeezed out of her. Then she grabbed her pencil flashlight and shone it into the corner.

“Great Glew!” The exclamation, part panic, part awe, came out of her unbidden, from the wellspring of racial memory.

Bonerot, great peeling sheets of it, coated the inside of the cavity, rolling away out of her sight. The places where supports were sunk into the bone were spongy-looking and deformed.

Rainbird had never seen anything like it, never even heard of an infestation so bad.

All the best alloys in the world wouldn’t keep the Day Sun up if the dragon skeleton itself were to collapse. There was no sunway without the bone.

And if there was no sunway, then there would be no sun. Only darkness and cold for the humans huddled beneath the dragon’s spine.

“And what were you doing so far into the cavity?” The supervisor steepled his fingers together under his chin, and lanced a sharp stare at Petrus. Turnworth was the supervisor’s name—and those soft fingers had never wrenched a P7 bolt into place nor held a blowtorch. A career bureaucrat. Petrus Gallavant hadn’t had much to do with him besides the exchange of reports, schedules, and paychits. He wasn’t happy to be here now, but he knew his duty.

Bonerot in the sunway!

“Sunmoss, sir.” Petrus stared woodenly above the man’s head. It was an effort to hold his head up, keep his spine straight. Luckily he had not been invited to sit down. He would not have been able to get up if had.

“Hmm.” Sunmoss was the inspectors’ prerogative, unwritten but customary. Even Turnworth could not say anything against that. “And you’re sure of the extent of the infection?” Turnworth glanced distastefully at the sample of spongy bone on his desk.

“I know what I saw, sir.” Against Rainbird’s vociferous protests, Petrus had climbed into the track and examined the bonerot for himself before reporting it to the supervisor. He had hoped she was wrong.

She wasn’t.

“And it was just you, Gallavant? No one else knows about this?” Turnworth’s narrowed glare seemed sharp enough to flay him open to his very soul.

“Just me and my assistant, sir.”

“Ah, yes. Your—assistant.” Was it just Petrus’ hypersensitivity about Rainbird, or did Turnworth emphasize that last word just a bit?

Turnworth leaned back in his chair and heaved a big sigh. “Bonerot. You do realize what this means to the Company? After the near collapse of Rib Six last year? And the pressure from the government and alternative energy competitors? If news of this got out to the press—well, the public outcry would be unimaginable!”

“We only have one sunway, sir,” said Petrus. “And the Company is the only entity that knows how to run it.” The Company—it had a name of course, but few people knew what it was—had been around for centuries. It had outlived whole states.

“Doesn’t matter if the sunway were rendered superfluous.

You’ve heard news of the Coronos Cooperative, yes? Claiming that the whatever-the-hell-ium metal they dig out of the ground is going to fuel another sun? That they’re going to send it up higher than the sunway and it’ll go around the world on its own?”

“Won’t work, sir.” Petrus knew his history. Other scientists and firms had tried for decades to come up with a suitable replacement for the Day Sun and its track. The public, when it thought about it at all, did not like living in the dragon’s skeleton, with its glowing eye gliding above them. Petrus could not understand such squeamishness. The dragon was long dead; the Day Sun was partially composed of its bioluminescent optical tissue but it hardly qualified as an eye anymore. Replace it with a sun that used violent, hard-to-control, and dangerous processes? Folly.

“It doesn’t mater what you think, or what I think,” said Turnworth, grimly. “What matters is that they have the ears of government officials and the press in their pockets. They claim they can open up the Dark Side to human settlement!”

“Thyrine won’t like that.” Everyone had their place: humans under the sunway, thyrine in the Dark Side and eiree up on the Perch. And the outcasts and the halfbreeds (my Rainbird!) on the sunway.

“It won’t matter if they get a sun shining down on the Dark Side. Men will move in. Men want to move in. The only thing holding the Coronas Cooperative back is the sunway and its smooth functioning. They’ll use the bonerot against us, if they can. Gallavant.” Now Turnworth leaned forward again. “You’re a Company man. Have been so for twenty seven years, it says on your record. Can we count on your loyalty—and discretion?”

Petrus hesitated, just a moment. Say nothing about the bonerot? What if the Company did nothing? No, that would be foolish. The Company wouldn’t ignore this, though if they hadn’t made those cutbacks the bonerot would not have turned into such a big problem. “Yes, sir.”

Turnworth had noted the check. His brows drew together. “Remember, Gallavant, if the spotlight should shine upon this bonerot, it will also shine on the discoverer—and those closest to him.” He glanced significantly towards the door.

Ironhand (Taurin's Chosen Book 2)

Ironhand (Taurin's Chosen Book 2) Flare: The Sunless World Book Two

Flare: The Sunless World Book Two Ghostlight (The Reflected City Book 1)

Ghostlight (The Reflected City Book 1) Mourning Cloak

Mourning Cloak Rainbird

Rainbird